From banding songbirds at Oak Hammock Marsh to watching bison at FortWhyte Alive, it was a day of Winnipeg nature for yours truly. I got to visit two destinations designated as Canadian Signature Experiences by the Canadian Tourism Commission, all the while appreciating Manitoba at a whole new level.

Oak Hammock Marsh Interpretive Centre

A 40 minute drive north of downtown Winnipeg is Oak Hammock Marsh Interpretive Centre, one of North America’s birding hotspots. The marsh is both restored bog and reclaimed agricultural land, and the entire site consists of 36 km² of wetlands, including a state of the art interpretive centre that was built 20 years ago.

Oak Hammock Marsh is not just a birding hotspot, but it’s also an important wildlife habitat. It’s home to 300 species of birds, 25 species of mammals, numerous amphibians, reptiles, fish, as well as countless invertebrates. Needless to say, ecologically, it’s a special place in Manitoba, and for nature lovers, it’s an absolute must!

There are so many different ways you can experience Oak Hammock Marsh, from going on walks along the boardwalk, to canoeing through the waterways, to learning and having fun in the interpretive centre. But I think the most fun way to discover Oak Hammock Marsh is by the high tech scavenger hunt better known as geocaching.

It was Jacques Bourgeois, the promotions and marketing coordinator at Oak Hammock Marsh (and all around amazing ambassador), who introduced me to the joys of geocaching. Jacques’ passion for sharing all the great things about Oak Hammock Marsh was infectious, and it was hard not to get excited as we explored the surroundings.

With a GPS in hand, we went to find three of the many caches hidden throughout the marsh. Each cache has its own name (ex: Frogs & Toads, Ground Squirrels, etc.), and then once you select a cache on the GPS, the GPS points you in the right direction of its location and tells you how far away you are from it, up to a 6m accuracy. When you’re within a few meters of the cache, you then start looking around for a possible hiding place. Without giving anything away, the caches are usually hidden somewhere sneaky, but not impossible to find. They’re often located in tupperware containers or plastic tubes, tucked away safely but well-marked.

When you open the caches, there’s a little logbook so you can write down your geocache name (which you can register online at geocaching.com) and the date you found it. There’s also a little piece of treasure – pins, pens, little toys, and so on. It’s geocaching etiquette to leave an item if you’re going to take an item, so it’s always best to come supplied with a few fun trinkets to leave behind.

What’s cool about geocaching is that all the while you’re hunting for the caches, you’re also exploring and learning about the surroundings. We meandered through the boardwalks and pathways through the marsh, spotting all sorts of wildlife. The ground squirrels were out in full force, squeaking away.

Jacques told me that the ground squirrels are true hibernators in the winter months. He demonstrated how slow their hearts beat when they hibernate by clapping “thump-thump”, and then waiting what felt like a minute before clapping his hands again. Crazy!

We also saw a shy thirteen-lined ground squirrel.

There were some handsome-looking Yellow-headed Blackbirds strutting about.

There were also many tiny toads hopping around, very cute!

Geocaching was a blast, but earlier in the morning, I did something equally as cool. After a delicious breakfast at the Interpretive Centre’s café, Jacques took me out to the marsh’s historic cabin to do some bird banding with Paula, the lead naturalist at Oak Hammock Marsh.

Bird banding is an activity that the public can also partake in when it’s offered, and all I can say is that if you’re a bird lover, it’s an experience you’ll never forget.

Earlier in the day, songbirds are taken from the nets located throughout Oak Hammock Marsh.

When they fly into the nets, they get tangled up and can’t get out. Don’t worry – the nets are only set up for short periods of time, and the naturalists regularly come to check up on any birds that might be caught.

If there’s a bird in the net, they’re gently untangled and are then placed in cloth bags to be brought back to the cabin. Delicately, the birds are handled by Paula so that they can be identified. They’re inspected for age, sex, the quality of their fat and feathers. Their wingspan is also measured. If they already have a band around their foot, we can look it up to add to the bird’s data file. If not, Paula adds the band around the bird’s foot so that the bird can be tracked. We banded four birds while I was there: a Sparrow, Common Yellowthroats, and an American Goldfinch.

After Paula’s done, she places each bird back in a cloth bag so that we could take them outside and release them. Jacques would open the bag, place the bird in my cupped hands, and then it was so cool to feel the little bird fly away from my fingers. Awesome!

Another cool thing I learned at the Oak Hammock Marsh: You can eat cattails! Here’s Jacques, who had just walked out into the mud to find a young cattail for me to try. Here he is demonstrating that you can crumble apart the tops and use them as flour in baking.

He then plucked out the cattail by the root, and peeled back the green to reveal a white shoot that you can eat! Crunchy like an apple, it was refreshingly and delicious and kind of tasted like cucumber. Yum!

Afterward we went back inside the Interpretive Centre. I was shown the rooftop where they have a garden growing full of indigenous species from the tall grass prairie ecosystem.

We went back inside and Jacques showed me around all the exhibits and displays. Did you know that the Oak Hammock Marsh is also home to Ducks Unlimited?

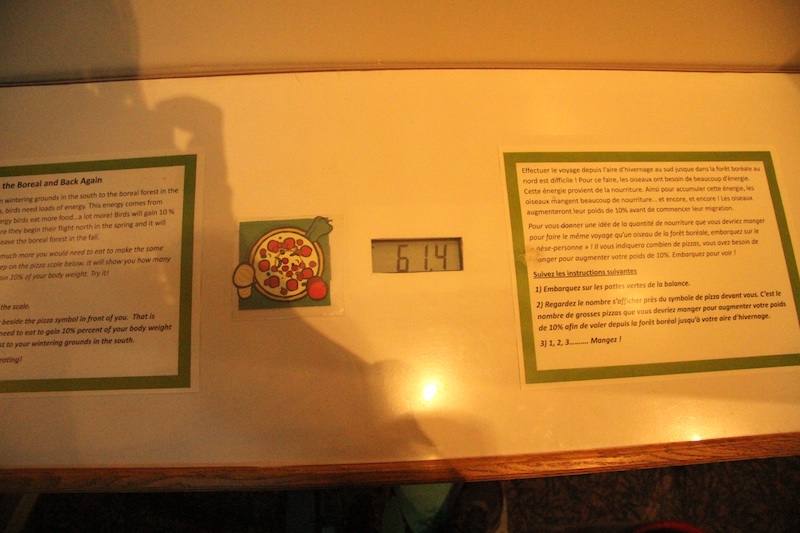

In the children’s area, there were all sorts of fun displays. Here’s one that shows you how many pizzas you’d have to eat if you were a migratory bird preparing for a transglobal migration. Based on my weight, I’d need to eat 61.4 pizzas… per day! Yikes!

I also got to have my wingspan measured. Jacques did the honours and it turns out I have the identical wingspan as…

… a Great Grey Owl! The Great Grey Owl also happens to be Manitoba’s provincial bird, which I thought that was a good omen for my travels throughout the province.

Although I could have easily spent the entire day exploring Oak Hammock Marsh, I had to get on my way to my next stop at the southeastern end of the city. Before I left, Jacques took me up to the café one last time to get a freshly baked out of the oven ginger snap cookie as a treat for the road. Have I mentioned that Manitoba hospitality is amazing?

FortWhyte Alive

Although FortWhyte Alive sounds like it could be an old fur trading post, it’s actually not, although the fur trade and Manitoba history certainly play a role. Located in the southeast of Winnipeg, FortWhyte Alive is more like a large park and recreational centre with a focus on environmental education and outdoor recreation, emphasizing Manitoba’s nature, history, and indigenous culture.

I was here to partake in their signature three hour tour called A Prairie Legacy: The Bison and its People. Led by Lisa Turner (FortWhyte Alive’s Tourism and Corporate Programs Coordinator), my tour consisted of a small group of visitors, all of us eager to discover how bison had influenced the history of Manitoba and the lives of aboriginals, Métis, and pioneers.

First things first: if you’re going to learn about bison, it’s probably a good idea to see some bison. We hopped in a small tour bus, and Lisa drove us into the bison enclosure, where we got to watch a herd of bison up close, but from the safety of inside the bus. It was a beautiful, awe-inspiring sight, and somewhat hard to believe that millions of these creatures once roamed all over the prairies.

Next, we took a short nature walk through the aspen forest. Lisa taught us that these aspen trees have a white powder on the south-facing side which, if you rub off and apply to your skin, can actually be used as a natural sunscreen (equivalent to 5 SPF).

At the end of the forest was an encampment of Plains Cree tipis, used as housing for the local aboriginal communities. The poles are made of tamarack, and the covering is made from bison skin.

Entering the tipi, we circled in the traditional clockwise tradition before sitting down to learn about how the Cree traditionally lived, including how they used the bison.

Several items were passed around, and we were asked to guess what they were. An orangey-brown waxy bar was handed around, and turns out, it was soap made from bison fat. There was a dried bison bladder, used as a water canteen, and then a bone structure that looked a bit like a violin bow, but it turns out it was a spear launcher called an atlalt. We all got to try launching a spear with the atlatl – it definitely goes much further than if you were to throw one without it!

From the tipi encampment, we strolled over to look at another traditional Manitoban house from the province’s early pioneering days: the sod house. The one room sod house made for a convenient (and well-insulated) dwelling in areas without forests.

Another legacy from Manitoba’s pioneering days is the Red River wagon. These wagons were entirely made of wood, and could be floated across rivers if necessary.

Canoeing on the lake in a voyageur canoe was another part of our experience on this tour. Voyageur canoes were used extensively throughout Manitoba’s river ways during the fur trade era, used to transport goods to and from the trading posts and to various settlements and encampments.

Although I don’t have much of a canoeing skill, it was fun to be out on the water, paddle in hand, manoeuvring the beautiful voyageur canoe across the lake.

Although the skies looked bleak, it never rained during our canoe trip. In the end it didn’t matter. After our canoe trip we rejoined around a covered bonfire pit where we learned the art of making bannock. Traditionally a Scottish flatbread (as in, it doesn’t require yeast), bannock was adopted by the indigenous communities and pioneers in Manitoba as a culinary staple.

First, you take the bannock dough and you roll it in your hands until it turns into a rope.

Next, you wrap it around the end of a stick, making sure it’s completely sealed at the end.

You then bake it over a flame, making sure you don’t burn it. It takes about 5-7 minutes.

When it’s ready, you let it cool, take it off the stick, and then fill it with whatever topping you’d like. I decided to opt for the Manitoba maple syrup.

To go with our bannock, Lisa brewed some rosehip tea, with rosehips foraged from the nearby forest. Rosehip tea is rich in vitamin C. It’s also used as a flavouring in many commercially-made herbal teas. With a delicate flavour, it was the perfect thing to sip on and enjoy. And it was hard to believe, but our three hour tour had come to an end.

A big thank you to Jacques at Oak Hammock Marsh Interpretive Centre and Lisa at FortWhyte Alive for hosting me during my July 2013 visit.